|

Three Steps, One Bow for Peace

With One Heart - An Evening with Heng Sure and Heng Ch'au

by Pavithra Krishnan - www.CharityFocus.org

Rev.

Heng Sure ordained as a Buddhist monk in 1976. For the sake

of world peace, he undertook a "three steps, one bow"

pilgrimage from South Pasadena to Ukiah, traveling more than

eight hundred miles, while observing a practice of total silence.

Rev. Heng Sure obtained an M.A. in Oriental Languages from UC

Berkeley and a Ph.D. at the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley.

He serves as the director of the Berkeley Buddhist Monastery

and teaches on the staff at the Institute for World Religions.

He is actively involved in interfaith dialogue and in the ongoing

conversation between spirituality and technology.

Rev.

Heng Sure

Berkeley Buddhist Monastery & Institute for World Religions

2304 McKinley Avenue, Berkeley, CA 94703

http://paramita.typepad.com

Three

steps and a bow. That's how they walked it. Two monks on a pilgrimage

of peace that took them through a series of wide-ranging encounters

and extraordinary experiences -- within and without.

In

May of 1977 Heng Sure and Heng Ch'au started their unique journey

from downtown L.A. to the City of Ten Thousand Buddhas in Talamage

near Ukiah. A journey of more than 800 miles that took two years

and nine months to complete. They bowed in peace, and for peace.

Touching their foreheads to the ground, opening their hearts

with one wish for the world. Peace. For everyone, everyday,

everywhere.

Three

steps ... and a bow.

More

than 20 years later, they sit in a living room amidst a small

gathering. And for the first time since that journey ended,

they speak of it together, sharing the stories and the wisdom,

the joys and the frustrations. What shines through is a compassion

and humility beyond words.

When

Heng Sure begins speaking, he asks one question: "What

brings us here tonight?" He answers it himself. “Curiosity

from the heart,” he says. And he is right. All of us came

with questions inside. Insistent internal questions -- But why?

But how? Because what these two did is not easily or immediately

comprehended by our minds.

Heng

Sure tells us it was their introduction to the Buddhadharma

through practice. "Road- tested you might say," he

twinkles. He talks of the pilgrimage having been a space where

they could more closely follow how the microworld of the self

influences the macroworld -- not only the one you encounter,

but the world that extends beyond. On their travels they took

no food with them, relying instead on the compassion of strangers

in strange towns. It was a humbling exercise in dependence and

vulnerability that led to a kind of trust and sensitivity. A

heightened awareness of what you're putting out and what's coming

back.

He

tells us a story then. Heng Sure is a wonderful storyteller

-- warm, funny and self-deprecating. This was the story of Heng

Sure the Sacred Monk out on the highway, bowing for world peace

and ... thinking about chocolate cake and a can of Pepsi. It

is the job of a meditator to watch his thoughts, and Heng Sure

watched them through a cycle of greed, anger, stupidity and

repentance. There was greed in his desire, anger in the can

of Pepsi that came flying out a car window making straight for

his head, stupidity in the broken glass in which it resulted,

and repentance in his heart as he came closer to understanding

how the choices we make determine the quality of life we encounter.

"Was

that a play written by the Universe for Heng Sure the Angry

Monk?" he asks. "I don't know."

But

the story isn't about crime and punishment. It is about recognizing

causes and their effects. It is -- to me -- about an awareness

and attentiveness to one's thoughts and actions and how they

come back to you. Marty would later say that the more peaceful

they became inside the better people treated them.

Marty

Verhoeven -- Heng Cha'u -- no longer in a monk's robes but with

the same wisdom and compassion. Where Heng Sure stopped, he

took over. A beguiling, irrepressible speaker -- and a keen

mind. Very. Heng Cha'u was the Dharma Protector on the journey.

As Heng Sure was under a vow of silence, Marty handled the provisions,

the press, the police -- the details. Man Friday, he calls himself.

Marty is also highly skilled in the martial arts. "Yes,

I was the Hu Fa," he says, "the Dharma Protector.

That means you protect ... with Dharma," he chuckles. "I

didn't really understand that." Thinking it only necessary

and natural to take a weapon or some form of protection with

them, Heng Cha'u approached his teacher. He was instructed to

take with him the Four Hearts. No dazzling defense moves or

surefire weapons. Walking into a troubled world of rage, violence

and turmoil, Marty's protection was ... the Four Hearts. (The

Merciful Heart expresses love for everything, the Sincere Heart

follows what is right, the Attuned Heart follows the natural

order of things, and the Dedicated Heart holds to the chosen

pursuit.)

So

that's what this black-belt and his companion walked forth with.

"If you use these you will find them inexhaustible,"

their teacher said. And they were sorely tested on this. Again

and again and again. People threw stones, punches, insults,

threats. Walking through some of the toughest parts of town,

they encountered dope-pushers, alcoholics, hardened street gangs

-- troublemakers at large -- aching for an excuse, any excuse

to fight. Looking down the barrel of a gun and meeting it with

the Four Hearts, that takes a certain sort of strength, an integrity

of spirit and unwavering conviction. That is what Heng Sure

and Heng Ch'au took with them. They say that is what kept them

alive.

"When

you're bowing, everything is in a different time," says

Heng Sure. "Things look different. Things change. And for

sure the Dharma comes alive when you need it." How else

to explain the timely interventions, the woman who stepped out

of a bar announcing that the drinks were on her just as a crowd

of aggressive drunks were getting ready for some roughhousing,

or the man who drove up to point out that the fennel being gathered

for fennel tea wasn't fennel at all but hemlock -- and enough

to drop a cow at that, or the Hells Angels waylaid in the nick

of time by the teacher himself, who spent a couple of hours

in the monastery and came out saying, "We promised the

old fellow to take care of you, so not to worry." How to

explain the children who gave them their lunches on their way

to school, or the people who drove miles to give them a bag

of groceries ... the stories go on, they are endless. They illustrate

how remarkable, how very unique this pilgrimage was.

But

then Marty says something that brings you to a dead halt. "Sitting

here, one of the things I felt was that none of you guys is

any different from us. You wrestle with the same things."

Taking

that in can take your breath away. Because it's one thing to

look at the two of them in wonder and awe of their journey and

its motivations, but it's quite another to realize that your

life and your road are not that separate from theirs. That yours,

too, from this perspective, is a bowing pilgrimage.

"There

is no distinction between bowing on the highway and the lives

we are leading now," he says. At the start of their journey

they were told to be on the road as if they'd never left the

monastery. When they returned they were told to be in the monastery

as if they'd never left the road.

Someone

would later ask about renunciation, about spiritual desire,

and whether that too had to be overcome. "Desire's a single

flavor," says Marty. And Heng Sure recalls how early on

his teacher would tell him repeatedly: "Forget the harvest.

As much as you seek, that's how much you'll be obstructed. Don't

seek Enlightenment. Just bow."

Before

the close of the evening, there is the Dedication of Merit:

Dedication

of Merit

May every living

being,

Our minds as one and radiant with light,

Share the fruits of peace,

With hearts of goodness, luminous and bright.

If people hear and see,

How hands and hearts can find in giving unity,

May their minds awake,

To Great Compassion, wisdom and to joy.

May kindness find reward,

May all who sorrow leave their grief and pain;

May this boundless light,

Break the darkness of their endless night.

Because our hearts are one,

This world of pain turns into Paradise,

May all become compassionate and wise

May all become compassionate and wise

Heng Sure tells us it is a gesture of grace, where you share

the blessings all the goodness the merit you have within. You

send it out to the world with a wish for wherever you see need

for wholesome change -- specific, general, personal or universal.

"The spirit of giving sends the gift, the prayer for well-being,

throughout the world, to all creatures as far as our minds extend."

On

his guitar Heng Sure plays the tune to which the Dedication

has been set. I am not sure what I am feeling, but it’s

overwhelming. This is what they did; at the end of every day,

these two, having walked long hours in their microworlds, they'd

turn it back, dedicate it outwards, give it to the greater world.

We,

who were not part of that journey, listened to them; and listening,

it became impossible to remain untouched, unmoved – not

implicated.

You

realize that they walked for the people you meet on the streets,

and the one's you've never seen and never will, they walked

for people they knew and the one's they didn't. They walked

for me -- and for you. And in that sense all of us were a part

of their journey.

There

is a rush of bewildered gratitude and a stunned feeling that

comes from trying to hold the enormity of what they did in your

head and in your heart.

"There

are many ways of bowing," Heng Ch'au has said. "You've

got to be creative."

We

caught a glimpse of a deep and true wisdom tonight. And there

seems to be only one thing left for us to do.

Just

bow.

"Excerpts" -

Three

Steps, One Bow - Journals

- - -

Heng Sure and Heng Ch'au

"

Three Steps, One Bow" --

Photo

Album

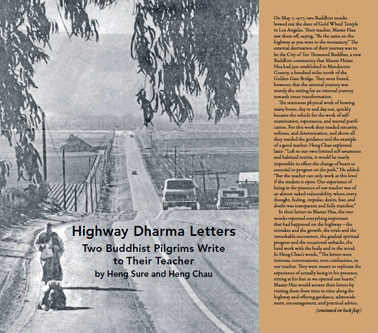

'Highway Dharma Letters'

- New Edition -

Buy @ Amazon.com

This collection of letters was written by two American Buddhist monks, Heng Sure and Heng Chau, during their two-and-a-half year pilgrimage for world peace along the California coast from 1977 to 1979. Bowing to the ground after very three steps, in the manner of early Buddhist pilgrims in China, they slowly made their way north, up the coast, from East Los Angeles, following Pacific Coast Highway through Santa Barbara and Big Sur to San Francisco, across the Golden Gate, then 100 miles further north on the Redwood Highay to Mendocino County and the newly established City of Ten Thousand Buddhas. Going at a pace of a mile a day, they bowed, studied, and wrote letters chronicling their experiences to their teacher, Tripitaka Master Hsuan Hua.

Rev. Heng Sure is currently director of the Berkeley Buddhist Monastery and teachers on the staff at the Institute for World Religions. He received a Ph.D. from the Graduate Theological Union. He is a professor at Dharma Realm Buddhist University.

Heng Chau, known as Martin Verhoeven, graduate with his Ph.D. from the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He is a professor at the Graduate Theological Union (GTU) and Dharma Realm Buddhist University.

Journal

Entry:

Great

Compassion comes when you stop picking and choosing among living

beings you cross over. What are these beings? How do you take

them across? The Sixth Patriarch's Sutra explains that

the living beings you take across are just the thoughts in your

mind, the thoughts that arise from your self nature. When the

Bodhisattva really does his work he crosses over all his thoughts

without discriminating among them. He can't take a vacation

at any time. He has vowed to take all beings (thoughts) across

to emptiness. The bodhisattva separates from thought and leaves

defilement:

The sentient one when enlightened

leaps out of the dust.

His six perfections and myriad practices

are nurtured at all times.

-- Master Hua

Ten

Dharma Realms

Great

compassion can manifest when one realizes that the self nature

is basically without any differences. It's all one and the same

substance and he is part of it; it's in the self-nature that

he connects with all that lives. This is where he does the work

of taking all beings across, taking all thoughts back to their

source.

When a single thought is not produced

The entire substance manifests.

The

Bodhisattva practices Great Compassion, and as he practices,

his realization increases. There is no realization without practice,

guided by vows. When he vows to take all living beings across,

his vow is the beginning of compassion. When he sends all thoughts

back to the self nature, that is actual practice. Why? Because

living beings are thoughts and thoughts are living beings.

The

master wrote this verse:

Truly recognize your own faults;

Don't discuss the faults of others;

Others' faults are just my own.

Being of the same substance

is called Great Compassion.

Your

own faults from failing constantly to take across living beings.

Being lazy and not working diligently is a big fault; it is

not the practice of the Bodhisattva.

Don't

discuss the faults of others. "Others" are just thoughts

in your own head. What you see as a fault in someone else comes

from your discriminating mind.

Others'

faults are just my own. You should return the light all the

time. Shine the light on the projections of the mind and get

to work crossing them over.

Being

of the same substance is called Great Compassion. All thoughts

come from the self-nature. When they filter up into the mind

they get discriminated into good and bad, right and wrong. When

the Bodhisattva practices Prajna wisdom and wipes away all thoughts

as they arise, he is returning to his self-nature, to the original,

fundamentally pure substance that he shares with all living

beings. This is truly taking all living beings across.

"At

all times he nurtures them." He must do it constantly for

Great Compassion to manifest.

"At

all times" in the Buddhist sense means from thought to

thought, minute to minute, hour to hour, day to day, week to

week, through months, years, life to life, kalpa to kalpa. Time

loses its meaning. For the Bodhisattva who has vowed to save

all living beings, one thought of purity, one act of Great Compassion

extends throughout all time and space to the ends of the Dharma

realm. What could be more liberated, more independent than the

scope of Great Compassion?

Practices

are the measure of the Bodhisattva. In order to stay on the

Middle Way he must maintain his Dharma-methods no matter what

circumstances arise. If a good state appears he cannot turn

from his practice. If an unpleasant scene develops, the Bodhisattva

nurtures his practice all the same, taking tender care of his

most valuable possession, the jewelled Dharma-raft that can

ferry all beings from suffering to the other shore of bliss.

Also

See:

Spiritual Practice for Personal and Community Peace

...Rev.

Heng Sure...

Buddhist

Bowing As Contemplation

...Rev. Heng Sure...

A

Buddhist Perspective on Fasting

Rev. Heng Sure

A

Buddhist Approach to Dreams

...Rev. Heng Sure...

Ballad

of the Dharma Doctor

...Rev. Heng Sure...

A

Monk's Day

...Rev. Heng Sure...

|