|

...Inner

Truths...

by

Brian Alterowitz

Photos

by Chad Harder

Very little about Buddhism is universal. There are as many different

paths of Buddhism as there are branches of Christianity,

each with its own take on what is true. For example, some practitioners

of Vipassanna don't consider what they practice a religion,

or even call themselves Buddhists.

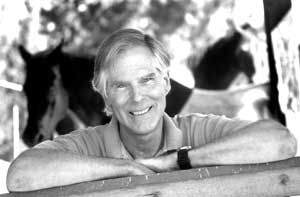

David

Perry doesn’t look 63 years old.

Frankly,

the man barely looks a day over 50, and only because of his

gray-white hair. Maybe it’s the brightness behind his

blue eyes or his easy, frequent smile, but he fills the room

with an air of youthfulness.

Perry

is one of a growing number of people in the Missoula, Montana

area who practices a form of Buddhism. While western stereotypes

often portray Buddhists as old people with shaved heads and

orange robes, many local people with very conventional upbringings

have found truth in the teachings of the Buddha and apply them

every day to their personal—and professional—lives.

Perry has been practicing

Vipassanna meditation for 10 years, a nonsectarian form of meditation

that concerns itself not with faith, worship or converting others,

but with removing suffering from people's life.

"The

Buddha said, "Don't believe me, don't believe anybody,

don't accept anything based on tradition. Don't believe anything

based on the fact that your community believes this or your

country believes this or the people that you are around believe

this,"" says Perry. "What the Buddha taught is

that there is suffering, and that [meditation] is a way out

of suffering."

In

a sense, Perry helps people find their way out of suffering

every day. He is a professional mediator in the Bitterroot Valley,

settling domestic disputes and custody battles. Mediators differ

from lawyers and judges in that they attempt to settle problems

out of court, and their decisions are non-binding. Perry’s

job is to get both parties to agree to the compromise. Although

Perry went to law school and practiced law for 17 years, he

eventually grew disenchanted with the profession.

"The

practice of law is based on finding different ways to describe

the same thing, either to put a rose tint on it or a black tint

on it," he says. "You're trying to restate reality

for a court or a jury."

To

Perry, truth and honesty are essential to both his life and

his profession. In fact, he finds that most of his work involves

finding a way through other people's misunderstanding and misinterpretation

of the truth. In his experience, a common thread runs through

all human conflicts: The stated cause of the controversy is

rarely what's really going on.

Perry

considers himself a practitioner of dharma, the teachings of

the Buddha. Dharma is also a Sanscrit word meaning "truth,"

which forms the foundation of his profession. The mediator often

has to work through a couple's resentments and petty differences

before he can address the problems at hand. Generally, when

his clients' unfinished business is taken care of, the problem

usually takes care of itself.

"The

dharma has helped me to see things the way they are," he

says. "The whole drift of how I practice mediation is to

try to really understand what is going on. Then I can bring

some effectiveness to [my clients] to help get beyond that."

Perry

isn't surprised that Buddhism has found a strong following in

the Missoula, Montana area, which reminds him of San Francisco,

California circa 1967, where he lived and practiced law for

years. He says the physical setting of western Montana is conducive

to spiritual rather than materialistic pursuits.

"There

are enough people here who have denounced the American Dream

as life's end-all and be-all," he says. "That seems

to have created an energy here that is particularly interested

in this kind of spirituality."

Vipassanna

has had other practical benefits for Perry as well. He comes

from a family of alcoholics, himself included. He started meditating

in January of 1987, and stopped drinking three months later.

It was only years later that he made a connection between the

two.

"Part

of what happens when you meditate is that painful emotions and

desires become less frequent visitors," he says. "You

generally become more and more content with the way things are."

In

1989, Perry picked up a book on Vipassanna meditation and was

immediately attracted to it, he says. Vipassanna, which literally

means "seeing things the way they are," has allowed

Perry to approach his work without preconceived notions,

a neutrality that is vital to his profession.

"Vipassanna

carried with it the unmistakable ring of truth," Perry

says.

The

pursuit of truth is one of the few things that the different

branches of Buddhism have in common. While most Buddhists follow

five basic precepts "avoid taking life, take only what

is given, avoid lies and hurtful language, refrain from sexual

misconduct, and avoid intoxicants" these ideas are by no

means universal.

In

fact, very little about Buddhism is universal. There are as

many different paths of Buddhism as there are branches of Christianity,

each with its own take on what is true. Some practitioners of

Vipassanna, Perry included, don't consider what they practice

a religion, or even call themselves Buddhists.

So

what is universal? Buddhism teaches that life's natural state

is suffering, and that the cause of all suffering is desire.

People constantly desire what they don't have, be it a big house

or a new car. Buddhism teaches that no matter how often someone's

desires are fulfilled, the person will never have lasting satisfaction

while they continue to desire.

Buddhism

is also a highly inclusive religion, which means that a person

can practice it and still be a Christian, for example, without

the two religions conflicting with one another. In fact, some

Buddhists see a great deal of harmony between Christianity and

Buddhism.

"If

you lay the three years teachings of Jesus Christ alongside

the 45 years of teachings of the Buddha, they really said the

same thing," says Deanna Sheriff, director of Osel Shen

Phen Ling, (OSPL) a local Tibetan Buddhist center. "Be

good and kind, try to help others. Be happy and you'll make

yourself happy."

This

kind of acceptance is an everyday part of life for Leslie McCormick,

a volunteer coordinator at Partners in Home Care Hospice. Her

job is to pair volunteers with people with terminal diseases

and try to make the patient's final months as happy and comfortable

as possible.

McCormick,

27, has been practicing Buddhism with the Rocky Mountain Buddhist

Order for the last four years. She is an energetic, friendly

woman who listens intently before answering questions. She talks

quickly, making sweeping gestures with her hands to illustrate

her point.

Being

understood is important to McCormick, and she makes a point

of explaining and re-explaining anything that may be vague or

unclear. She resists lingo and labels, saying that people who

overuse them either aren't very creative or don't know what

they're talking about.

McCormick

was raised Catholic, but says that as she grew older, the religion

became less and less relevant to her life.

"It

was just becoming clearer and clearer to me that it was just

not reaching a depth in me, that I was not clicking with people

on a level I wanted to," she says. "Things were just

feeling less and less synchronized."

Although

McCormick began to go to church less often as she grew older,

she was not trying to divorce spirituality from her life. Actually,

being raised Catholic gave her a strong desire to seek out a

belief system that she could believe in.

Buddhism

made the most sense to her because it brought with it a sense

of personal responsibility. In Buddhism, McCormick explains,

there is no parental god-figure looking down upon you, punishing

you if you do wrong and praising you if you do right. Each person

is responsible for making decisions in his or her own life.

In addition, Buddhists aren't waiting around on this earth to

go to heaven, but are constantly working toward a goal.

"Instead

of waiting for the end to find out what happens to us, moment

by moment we look at our mental states and pay attention to

the consequences in our lives and other people's lives,"

she says.

After

getting her degree in creative writing at the University of

Montana, McCormick looked for a job where she could help people

and seek a better understanding of Buddhism. Working at the

hospice, she says, does both.

While

it might seem that working with the dying for long periods of

time "especially those who die young" would shake

a person's religious beliefs, McCormick finds that her work

actually strengthens her beliefs. Buddhism teaches that all

life is transient, that nothing stays the same for long. By

working with people in their final days, McCormick confronts

this reality every day.

"We

all know intellectually that we are going to die, but most of

us don't know it on a deep level," she says. "My work

takes what I know intellectually and helps me to understand

it emotionally."

Buddhism

also teaches that none of us is substantially different from

any other being, but that our ego prevents us from seeing this.

In her work, McCormick has to deal with people letting go, not

only of their egos, but of the very things that once defined

them. For instance, a man who used to walk every day of his

life might now be confined to a wheelchair; an athletic father

might not be able to play ball with his son anymore. This knowledge

that, in death, we must all let go of how we lived, has helped

McCormick understand her own ego.

"We

all want assurance from the world around us that we are real,

that we have our own identities," she says. "But this

is essentially not the case. What I am is not any kind of essential

thing, but is defined by my environment."

More importantly, says

McCormick, her work keeps her thinking and living in the present.

She can't worry too far in advance, because her patients simply

don't have that luxury. Being forced to live in the moment reminds

her of how precious life is.

"This

work takes you down to the most real level of human interaction,"

she says. "You see so much amazing love and change and

suffering that it allows you to put your life in perspective."

|