The Los Angeles Buddhist-Catholic Dialogue:

An Early Journey

Buddhists and Christians have lived among each other from the early years of Christianity. Small

communities of Christians existed in India, possibly as early as the first century C.E., and certainly

by the 7th century, at which time there was also a Christian community in China, but records of dialogues

between these communities have not come to light. At the beginning of the modern era, the European

voyages of exploration and the subsequent expansion of commercial and colonial powers in Asia set the

stage for the first major encounter between these religions. The explorers as well as the missionaries who

accompanied them saw themselves as part of a divine mission to spread the gospel; they brought the word

of God into Asia, but they also instituted European structures of power and domination over the

indigenous peoples, Buddhists, as well as Hindus and members of other religions. This was not an

atmosphere which fostered true dialogue.

Today something new is occurring in the relations of these two religions. In this city named after the most

sacred "Queen of Angels" of Christianity, large Buddhist and Christian communities live side by side. the

great wave of Asian immigration into Los Angeles coincided with a new openness towards other religions

in Catholicism, promulgated by the decree, "Nostra Aetate," (Declaration of Non-Christian Religions) of

the Second Vatican council in 1965. It set the stage for a real dialogue.

In Los Angeles a unique situation for Buddhism developed. All the major Buddhist schools and ethnic

traditions, each with its own language and customs, are found here. The great diversity within Buddhism

stimulated inter-Buddhist dialogue. In 1980 the Buddhist Sangha Council of Southern California was

formed, the first such Buddhist organization to embrace all forms of Buddhism. The Sangha council,

while establishing its own dialogue among Buddhist groups, began to explore inter-faith dialogue.

During these years the Roman Catholic community followed through with the guidelines of Nostra

Aetate. In 1969 the Catholic Archdiocese of Los Angeles with other religious communities founded the

Interreligious Council of Southern California; in 1971 Buddhist communities joined. In 1974 the

Archdiocese formed the Commission of Ecumenical and Interreligious Affairs to coordinate and expedite

its relations with other religious communities. Through the Commission and the Council of Interreligious

Affairs one on one exchanges began between Catholics and Buddhists. Some highlights of these exchanges

included the fifteenth anniversary celebration of Nostra Aetate in 1980; the twentieth anniversary in

1985; the 1986 Los Angeles observance of the assisi World Peace Day; and the multireligious celebration

of the 1987 visit of Pope John Paul II in Little Tokyo, "Nostra Aetate Alive." This history of cooperation

laid the foundation for the Los Angeles Buddhist-Catholic Dialogue, which began February 16, 1989.

The Buddhist Leaders of Los Angeles agreed to enter the dialogue in spite of some feelings of reticence.

Fears and distrust of Christians formed during the colonial period still linger among much of the

Buddhist population. Nevertheless, some of the Buddhist leaders had developed friendly relations with

leaders of other religious groups, particularly with the Roman Catholics, and were able to assuage the

fears of their colleagues. The Buddhist community saw this dialogue as an opportunity to help increase

understanding and sympathy toward Buddhism, a process which could be helpful to the Buddhist

community.

There was also the tradition of Buddhism in the course of its long history to work with other religious

groups. Since the essence of Buddhism is to abandon all forms of attachments, its hallmark has been not

to criticize or condemn any other religion. The Buddha himself often visited other religious centers and

leaders, and followers of Buddhism have often been encouraged to study and experience different

systems of religion or philosophy.

Among Catholics, Nostra Aetate initiated a fundamental change in the way the Church viewed other

religions. For the first time it encouraged dialogue with them. A profound rethinking and appreciation of

the intrinsic validity of other religions has gone on; Catholics have become eager to explore and learn

about other religions. Dialogue for both groups became timely and appropriate.

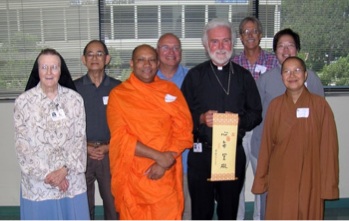

The dialogue is sponsored by the Buddhist Sangha council and the Catholic Office of Ecumenical and

Interreligious Affairs. It was formed as an official, on-going, core group dialogue. The core group was

designed to accommodate approximately eight Buddhist representatives and eight Roman Catholic

representatives. Meetings were to be held every six to eight weeks, rotating between Buddhist and

Catholic locations.

The committee from the beginning recognized that this was a very early and preliminary dialogue, with a

great need for mutual patience and simple getting to know one another. We have become aware first hand

that we have gifts to give each other and we have gifts to receive from each other. Herein lie some of the

first fruits of our dialogue.

The Essence of the Journey

There are vast differences in our histories and spiritual lives. Yet, we all entered the dialogue with a spirit

of openness and the expectation that we could understand each other; we were not disappointed. Our

dialogue experience unfolded into four dynamic processes.

First, we discovered that learning about each other's tradition was learning the vocabulary that it uses to

express itself. This proved to be more difficult that we expected, because the vocabulary comes from such

different worlds. Many words have no reference in the other tradition. For example, Buddhists were

perplexed with the Christian notions of soul and creator God, while at the same time, Catholics had great

difficulty with the concepts of anatman (no-soul) and a cosmos without a God. At times we spent an entire

session on just one word or concept. We learned not to attempt to cover a lot of material in a single

meeting, for we found it took time to get in-depth understanding.

Second, while each dialogue session has brought us some knowledge and understanding of the other's

tradition, at the same time we discovered that we were re-encountering our own. The novel questions and

fresh approaches required us to look anew at our own traditions, to see inconsistencies, to discover what

we needed to think through, it challenged us to articulate to one another what we took for granted among

ourselves. Sometimes this gave us a whole new perspective on our own beliefs. We expected to be teacher

of each other, bet became students or our own traditions.

Third, there were discoveries. Catholics unexpectedly learned about the negative attitude towards

Christianity among Asian Buddhists, the legacy of Christianity's involvement with western colonialism,

which began in the sixteenth century and continued in parts of Asia for more than four hundred years.

This legacy made all the more powerful the Buddhist's discovery of the extraordinary practice of

compassion exemplified in the life of Jesus in all its simplicity and beauty. At the same time Catholics

discovered how important compassion is in Buddhism, as comparable in its transcendence to divine basis

of love in Christianity. We discovered in the lives of simplicity and compassion shared by the founders of

our religions something basic to both. it is noteworthy that in spite of the differences, we share something

so fundamental in our orientations. This brought up the mystery of how our traditions could share

something so important, yet come from such radically different origins.

Fourth, sometimes even after spending a whole session on a word, we found that we could not

understand it completely. At the same time, we also found that we could continue to speak and to hear

each other even if we did not have a precise understanding of each other. Nonetheless, we have the

expectation that if we continue to talk with each other long enough, we will.

Among the topics we discussed were concepts of love: the Buddhist four Brahma Viharas (sublime states

of living) of Metta (loving-kindness) , Karuna (compassion), Mudita (sympathetic joy) and Upeksa

(equanimity) were compared to the Christian concepts of Eros, Philia and Agape. We also discussed

concepts of Soul and No-Soul (anatman), of resurrection and rebirth, and of Gnosis, saving knowledge.

Looking for common points of reference has turned out to be more difficult that one could imagine. But,

in view of the compassion central to each tradition, a concern for the welfare of all beings stands out.

Each tradition seeks to draw people towards a greater, purer more loving reality than that found in the

ordinary human context of life, so that they may realize their full potential.

The great models of this process in both traditions are their founders, who provide the key to the

spiritual life of their disciples. The importance of the founders can be seen in their lives of their disciples.

The Buddha and the Christ

The Buddha: the "Awakened One." born Siddartha Gautamma, a prince of the Sakya clan in northern

India, c. 624 B.C.E.

Through his own efforts he achieved Enlightenment, the realization of ultimate reality (truth), perfect in

wisdom and compassion. He set the Wheel of the Dharma in motion, showing all humankind (and

ultimately all sentient beings) the way to attain release from suffering and attain Nirvana, that ultimate

state beyond all description.

The Christ: the "Messiah," or "Anointed One," born Jesus of Nazareth in Judea; crucified outside of

Jerusalem by Roman authorities, c. 33 C.E.

Anointed by God to save humankind by death on a cross and resurrection from the dead, God became

human so humanity could be divinized. He was the total and complete manifestation of God, the Son of

God, the second person of the Trinity.

Past and Present

Buddhist

The Buddha was born in northern India of a princely family, as Siddhartha Gautama of the Sakya clan. His

mother died when he was one week old and he was raised by his stepmother and trained to become the

successor of the kingdom. He married and had one son. Leaving home at age 29, he gave up his princely

life and became a wandering ascetic, seeking the answer to the question of why people suffer. At age 35,

finding that extreme asceticism brought him no closer to enlightenment than did an indolent, luxurious

life, he turned to the middle path of moderation. He attained enlightenment by turning his meditation

inward, achieving the realization of ultimate reality and becoming "The Buddha," the Awakened One.

In his enlightenment experience the Buddha discovered the Four Noble Truths, the causes of and

methods to eradicate "dukkha", unsatisfactoriness, which underlies all life. He then "turned the Wheel of

the Dharma" (began teaching the Path to enlightenment/liberation) and devoted the next 45 years of his

life teaching others so that they might also attain liberation from suffering. He died at age 80 and entered

into parinirvana, ultimate reality, that state of complete peace and quiet that goes beyond concepts of

existence or nonexistence.

Buddhism does not recognize a beginning or an end to the cosmos, but rather recognizes that there is a

non-ending arising, maturing and dying of universes, all by natural law rather than by a primary cause.

Thus, many different Buddhas have existed in many different aeons in many different universes. All

sentient beings have Buddha nature, the potentiality of attaining enlightenment. While it would be

difficult for a non human to become a Buddha, all beings still have the potentiality of that potentiality of

achieving human form and eventual enlightenment. What distinguishes a Buddha from other enlightened

beings is that the Buddha has achieved supreme enlightenment, and so has discovered the truths that

Sakyamuni also discovered, and initially expounds the Dharma in a universe or an age.

Thus, while Sakyamuni is the historical Buddha of our time period and is honored by all, in some

traditions the central figure is not Sakyamuni, but a different Buddha. The most popular of these is

Amitabha Buddha, Lord of Infinite Life and Light, and he is venerated as the central Buddha in the Pure

Land schools.

As Buddhism spread from India to other countries, outward appearances changed as it took on

indigenous ethnic characteristics. Eventually three major Buddhist traditions emerged. Theravada (the

School of the Elders) became most prevalent in south and southeast Asia: Sri Lanka, Thailand, Burma,

Cambodia and Laos. Mahayana (the Great Vehicle) emerged as a major tradition around the second

century C.E. and spread into east Asia: China, Korea, Japan and Vietnam. By the eighth century C.E., the

third school, Vajrayana (the Diamond Vehicle) merged in central Asia: Tibet, Nepal, Bhutan, Mongolia

and eventually southern Siberia. By the twelfth century, virtually all of the specific schools within

Buddhism were well developed into their modern form.

While Theravada remains a fairly cohesive whole, it is more conservative in its attitudes and resembles

most closely the Buddhism practiced during the Buddha's life time. Mahayana Buddhism added more

scriptures to the canon, presenting the Buddha's teachings from a more non dualistic view of reality.

Vajrayana Buddhism added some elements of Tantrism* (esoteric, mystical rituals). Each developing

school added layers on to the already existing canon, so that changes in practice come not only from an

interpretive base, but from a canonical one as well.

Catholic

Jesus of Nazareth lived for approximately 33 years at the beginning of the Common Era in Judea and was

crucified by Roman authorities. He was a Jew, and he collected around himself a community of disciples

who discovered that in this Jesus of Nazareth, YAHWEH, the God of Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, and Moses,

the God who had revealed himself historically to the Jews, had become completely human. They

recognized Jesus as the Son of God, the Christ, the Messiah prophesied in the Bible and expected him to

return to institute the Kingdom of God upon the earth. His life of proclaiming the Kingdom, his healing

and forgiving, his passion and death upon the cross, and his resurrection from the dead, were the

ultimate revelation of God and established for eternity God's identification with humanity and the means

of humankind's redemption from sin and death.

The community of disciples, inspired and graced. by God's Holy Spirit, proclaimed the salvation found in

the Christ to the world, a proclamation that has never ceased. Christ has been proclaimed on every

continent, in every culture: Each ethnic group has found in Jesus something uniquely its own which they

celebrate through their own cultural genius and add, in this way, to the ongoing revelation of the Christ.

In the world today, great spiritual creativity is being expressed by "Third World" Christianity: that of

Asia, Africa, and Latin America.

Though originally persecuted in the ancient world, faith in Christ became the foundation of Western

civilization. Throughout the Middle Ages this faith was perpetuated in the hierarchical structures of

bishops, patriarchs and popes; in the heroic spirituality of monastics; in the theology debated and refined

in the great universities of medieval Europe; and in the devout lives of countless individuals, serfs and

nobles alike. In the eleventh century, with the breakdown of the old Roman Empire complete, theological

and political disputes which had long threatened the unity of the eastern and western branches of

Christianity resulted in the tragic separation of the Church of Rome from the Churches of the East. At the

beginning of the modern era, a renewed understanding of the prophetic ministry of Jesus was expressed

in the Protestant Reformation. Protestants, contending that Christianity should never be tied to a single

institutional expression or interpretation, broke with the Roman Church and western Christianity was

splintered. Today there are three major branches of Christianity: Roman Catholicism, Eastern

Orthodoxy, and Protestantism. Each community contributes, in its own capacity, to the presence of Christ

as the divinely transforming agent and goal of human history. Across the ages, he remains the Alpha and

Omega of history, the baby born in poverty, the preacher proclaiming a coming reign of peace and justice,

the prophet offering himself on the cross, the suffering servant and glorified Lord of humanity, its judge

and savior.

The Founder and the Follower

Buddhist

The Buddha, either sitting in meditation or standing to teach, is the usual image that adorns Buddhist

altars and shrines. As the Buddhist follower looks upon this image of the serene figure and the

compassionate, smiling face, he/she again pays homage to the teacher, the great enlightened one, who

shows the way of peace and spiritual development to all. To him is given the greatest reverence, for he has

shown the way to liberation. He is not a god, nor is the Buddhist concerned with god concepts. He is the

human teacher, one who has raised himself out of all suffering and attained perfection and has revealed

that path which can be followed by any person. In some Buddhist schools, emphasis is placed upon "self-

power" and the individual strives for perfection and enlightenment. In other schools, the individual seeks

guidance and assistance from Amitabha Buddha or one of the great Bodhisattvas (highly developed

spiritual beings who devote their lifetimes to helping others) for help in attaining that state which leads to

enlightenment

Buddhist practice is three-fold: ethical behavior, mind development and intuitive wisdom. Ethics is

usually seen as the foundation for all Buddhist practice. To proclaim oneself as a Buddhist is to willingly

take on the practice of certain precepts as a guide for behavior. The way in which a follower determines

whether any particular action is moral or not rests upon the ultimate question: "Is this behavior harmful

to myself or others? Is this behavior beneficial for myself and others?" One should always act in ways

which are wise, ways which are non-harmful to oneself and others. Besides trying to act in non-harmful

ways in body, speech and mind, one also strives to develop the perfections of generosity, ethical behavior,

patience, spiritual endurance, mental discipline and wisdom, as well as the development of the Four

Noble states of living: loving kindness, com passion, sympathetic joy and equanimity.

Serious Buddhist practitioners constantly examine their behavior to discover their strengths and

weaknesses. They attempt to strengthen those behaviors which are wholesome and to discourage those

which are unwholesome. There is always the awareness that the precepts cannot be kept perfectly; guilt is

discouraged as counter productive. The precepts are not commandments, but are guidelines for living a

wise life. Thus, Buddhists do not sin if they break a precept, rather, they have behaved in a harmful way,

the results of which will return to them.

The second aspect of practice is mind development, which is considered necessary for Buddhist practice.

Meditation, or the practice of mindfulness or awareness, helps the individual to calm the mind and free it

from self-involvement and self-attachment, from ideas and emotions. The practice of meditation helps a

person to observe how the mind functions and to produce understanding, to experience insight, and

eventually liberation. Meditation is not an activity that is done only at a special time. Meditation is the

state of mind of one-pointed concentration, of awareness and mindfulness, that allows one to see clearly

without the mental fetters of me and mine" which usually determine the way one perceives reality. While

sitting meditation is extraordinarily important in some traditions of Buddhism, in others self-awareness

is developed through other practices.

Rituals, chanting, and practice of mindfulness during daily life are important tools in helping the

individual to develop disciplined behavior. Thus, Buddhists perform pujas or offerings to the Buddha, in

order to recall his great virtuous qualities and to remind them of their spiritual goal. Prostrations are

done to help lessen pride. Chanting and study of the sutras is also an important part of developing

discipline and understanding.

The third part of practice is the development of intuitive wisdom that comes only when one can break free

of the three poisons of greed, anger and delusion. And this can occur only when we understand that there

is no separate identity, no self, no soul. Only when we see that our ordinary perception of things is an

illusion, coming from a self-centered deluded mind, can we hope to experience complete ultimate reality.

Catholic

The crucifix, the image of Jesus dying upon the cross, is the universal symbol of Catholicism. To gaze

upon it is to witness the horror of what humanity can do to itself, but at the same time, to see the power

of God's love to save humankind through it. To see the dying Christ is to see God in the most vulnerable

form of humanity, and, at the same time, humankind's hope of reconciliation. He is the path to our union

with God and imitation of him, the key to our salvation. "Love one another as I have loved you," Jesus

said. "Take up your cross and follow me."

Though the crucifix is displayed in many places, the richness of its meaning and power is most visible

when it stands over the altar. Upon that altar, as the head of the congregation gathered in the church, the

priest celebrates the Eucharist, the sacrament of the suffering, death, and resurrection of Jesus. He

repeats the words and gestures of Jesus at his last meal, when, with his disciples, he broke bread and

shared wine, identifying them as his body and blood about to be broken and shed to redeem all humanity.

"This is my body; this is my blood," speaks the priest as Jesus did that night. The body he speaks of is the

body of Christ upon the cross and also glorified at the resurrection; it is the bread he consecrates; it is the

congregation participating; it is the world-wide Church and all Christians who have ever lived; in all of

these Jesus is fully present. Each Eucharistic celebration renews and reactualizes the central mystery of

Christ's conquest over sin and death in which all Christians participate as members of the Body of Christ.

At the center of our lives as Christians is the sacramental unity of life in Christ. We became Christians

through the sacrament of Baptism. In earlier times the person was fully submerged in water, a kind of

symbolic burial, and then raised up again, symbolically resurrected with Christ. It means a new beginning

-- a new life -- a life of union with Christ. This participation in the death and resurrection of Christ is a life

long process, not completed until our own deaths and resurrection. It is a process of personal purification

and divinization, but the process ultimately includes the cosmos itself. The presence of the resurrected

Christ is drawing all of humanity and the cosmos towards a final reconciliation with their creator, towards

a new creation.

To sign oneself with the cross, as we do, is to take up a life of exemplary love. It is especially to take up the

cause of those who have no one else to act on their behalf, the powerless and oppressed, for they are

humanity at its most vulnerable. Christian spirituality must be manifested in involvement with one's

social community and in the pursuit of justice. "Whatever you do to the least of these, you do to me,"

Jesus said. The pursuit of justice and concern for others imitates the earthly life of the Christ.

Reading scripture and praying are the other chief practices of our spiritual lives. Both are done as

encounters with Christ. The Divine Office, for example, consisting of prayers and scriptural readings, is

the daily offering of the Church itself to God. The practice of meditation and contemplation, which dates

from the earliest years of the Church, continues to enrich the lives of Christians today. Through such

prayer one can be drawn to the highest levels of prayer, mystical union with God. In recent years

Christians have found certain practices from the Buddhist tradition helpful and consistent with their own

tradition.

Original Dialogue Members

Catholic Members

Msgr. Royale M. Vadakin, Co-Chair: Commission on Ecumenical and Interreligious Affairs

Sr. Thomas Bernard, CSJ: Archdiocesan Spirituality Center

Br. Lucius Boraks, CFX: Alemany High School: Commission on Ecumenical and Interreligious Affairs

Dr. Michael Kerze: Loyola Marymount University

Rev. Flavian Wilathramuwa, CMF: San Gabriel Mission

Buddhist Members

Ven. Dr. Havanpola Ratanasara, Co-Chair: Buddhist Sangha Council of Southern California

Ven. Dr. Karuna Dharma: International Buddhist Meditation Center

Rev. Masao Kodani: Senshin Buddhist Church

Ven. Walpola Piyananda: Dharma Vijaya Buddhist Vihara

Ven. Phra Setthakit Samahito: Wat Thai Temple

Mrs. Heidi Singh: Dharma Vijaya Buddhist Vihara

Ven. Dr. Thich Man-Giac: Chua Vietnam Temple

Edited by Ven. Karuna Dharma and Michael Kerze Ph.D.

(Published by the Buddhist Sangha Council and the Archdiocese of Los Angeles © 1991)