Dialogue Interreligieux Monastique / Monastic Interreligious Dialogue

Monks in the West III

“Monks in the West” is a gathering of Buddhist and Catholic monks in North America who come together to reflect on the challenges of living the monastic life in an increasingly secular and materialistic Western culture. It held its third meeting October 8-11, 2012 at the City of Ten Thousand Buddhas, about 110 miles north of San Francisco.

The City of Ten Thousand Buddhas is one of the first Chan (Chinese Zen) Buddhist temples in the United States and one of the largest Buddhist communities in the Western Hemisphere. It is also where the first Monks in the West gathering took place in October 2004.

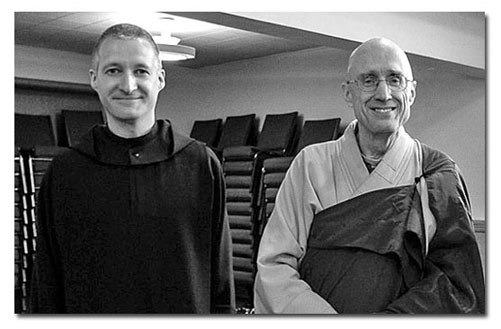

The conveners and primary planners of this third meeting of Monks in the West were, (left) Brother Gregory Perron OSB of Saint Procopius Abbey in Lisle IL, President and Chair of the Board of the North American Commission for Monastic Interreligious Dialogue and (right) Dharma Master Heng Sure, monk of the City of Ten Thousand Buddhas and Managing Director of the Berkeley Buddhist Monastery. Seven Catholic and eight Buddhist monks participated; many of them had taken part in Monks in the West I and Monks in the West II. The Catholic monks represented the Benedictine, Camaldolese and Cistercian branches of Western monasticism. The Buddhist monks were from the Chan, Thai Forest, Vietnamese Zen, and Soto Zen traditions.

The general topic for this meeting was monastic formation. There were no formal presentations; rather each session over the three-day period was devoted to an open discussion of one of the following sub-topics:

initial formation for monastic life;

monastic formation for lay associates;

why people are drawn to the monastic life and why they leave;

generational differences within the monastic community;

monastic mid-life crisis and senior monastic burnout;

care for the aging and dying;

technology and modern means of communication.

Reflection on these topics quickly and easily evolved into personal conversation that was marked by a willingness to speak honestly and openly of our actual experience of the monastic life. Rather than theoretical discussion of the “meaning of monasticism for our time,” participants spoke in the first person to describe the benefits and challenges of living the monastic life and trying to find authentic ways to give contemporary expression to traditional monastic teachings and values.

For me, at least, one of the most moving and enlightening moments came during our conversation about monastic mid-life crisis and senior burnout. Several of the participants, Catholics and Buddhists, described their disappointment, even disillusionment, with monastic life. They had become monks in search of—and fully expecting to find—what our two traditions would refer to as enlightenment, holiness, freedom, or selfless love. Instead, they were becoming more painfully aware of the depths of their own weaknesses and limitations, and the apparent inability of monastic practices to transform them into the image of their aspirations. They were, it might be said, coming to a personal realization of the reality of monastic life as described—in admittedly Christian terms—by the Cistercian author, Michael Casey:

"Monastic life is not really about self-realization, in the immediate sense of these words: it is far more about self-transcendence. These are noble words, but the reality they describe is a lifetime of feeling out of one’s depth: confused, bewildered, and not a little affronted by the mysterious ways of God. This is why those who persevere and are buried in a monastic cemetery can rarely be described as perfectly integrated human beings." [1]

We zeroed in on the fairly common sense among middle-aged monks of being “disillusioned” by monastic life. As our conversation continued, it became more and more clear that it was a good thing—though definitely not an easy thing—to be “dis-illusioned”—stripped of our illusions, not only about monasticism, but about human life. As our Buddhist brothers pointed out, the goal of the monastic life is freedom: freedom from lust, hatred, and illusion. To be disillusioned is to recognize the truth that I stand on no ground, to discover how dependent I have been on everything around me, to realize that everything I was looking for, had I found it, would have been a substitute.

Back Row - Br. Luke Devine / Fr. Michael Peterson / Ajahn Yatkio / Br. Gregory Perron / Fr. Cyprian Consigilo // Not Shown - Rev. Master Jisho

Front Row - D.M. Jin Young / Fr. William Skudlarek / Ajahn Guna / Fr. David Brock / Rev. Heng Sure / Kusala Bhikshu / Ajahn Jotipalo /

Br. Lawrence Morey / Rev. Berthold Olson

At the end of the day, if we end up with truth and acknowledge it, that is good, even though we may feel disappointed, disillusioned, and even totally lost. As one of the Catholic monks noted, the opening lines of Canto I of Dante’s Inferno can help us see a mid-life crisis not as a reason for throwing in the towel, but as a call to rediscover the path that had been lost:

Nel mezzo del camin, di nostra vita,

mi ritrovai per una selva oscura,

che la diritta via era smarrita.

◊

Midway upon the journey of our life

I found myself within a forest dark,

For the straightforward pathway had been lost.

The praxis, skopòs, and télos of Monastic Life

Monks in the West III reinforced an idea that emerged from our second meeting in 2007, when we dealt with the monastic practice of celibacy. The bromide about adherents of different religions being on different paths, but all walking to the top of the same mountain, did not seem to be an adequate way of describing the experience of Buddhist and Christian monks. Taking into account the remarkable similarities between our two ways of life, it might be more accurate to say that we are all on the same (or, at least, very similar) path, but moving toward different destinations.

At Monks in the West III, as we reflected on our experience of being formed in the monastic life, we again recognized that the rough and smooth places on the monastic path, whether Buddhist or Christian, are very similar, even though our way of describing our destination may be quite different. One of the participants proposed that we think in terms of the Aristotelian categories of praxis, skopòs, and télos.[2] Our monastic practices are very similar, as are the ups and downs of monastic life. We meditate, recite and chant sacred texts, wear distinctive garb, do not amass possessions, do not marry. In fact, our praxis is as much about what we do not do as what we do do. A monk is essentially a renunciant. Going without and doing without is the monastic way.

Our skopòs is also remarkably similar. We promise to go without and do without because we are aiming for freedom. We recognize that the more attached we are to ego, pleasure, and possessions, the less free we become.

Where we differ, however, is with regard to our télos, or at least with the way we conceptualize and describe the goal that draws us—the télos that “may be either conscious or subconscious . . . works even unintentionally . . . is not arbitrary, but resides in activities as a submerged, enfolded, and implicit causa formalis.”[3] When Christians describe the télos of monastic life, they speak of loving union with God, or being given a full share in the risen life of Jesus “forever and ever.” Such language elicits little if any response from the Buddhist. Christians, on the other hand, find it difficult, if not impossible, to relate to Buddhist language about putting an end to suffering by escaping from the cycle of rebirth.

It is certainly appropriate for theologians and philosophers to examine more closely the way Buddhists and Christians conceptualize and describe their respective téloi, and to try to determine if they really are different realities, and not simply different ways of describing the same reality. There may even come a time in our monastic dialogue when it will be appropriate to move beyond our present and, I believe, highly commendable, attitude of respect for one another’s understanding of the télos to which we hope to arrive at the end of our monastic journey, and to grapple with what it would mean if we came to the conclusion that these téloi are essentially different. For the present, however, it seems right that we concentrate on sharing our respective traditions regarding praxis and skopòs, and in this way encourage and support one another in reaching the télos that drew us to embrace the monastic life and that continues to illuminate our path.

Other Activities

Each day began at 6:00 AM with an hour’s meditation—that is, for those who were not up to joining the monastic community of the City of Ten Thousand Buddhas for an hour of chanting at 4:00 AM. On the second day the meditation was guided by a Buddhist monk, on the third by a Catholic. At 5:00 PM each day, a Mass was celebrated in the large Buddha Hall, which was attended by a good number of students from the City of Ten Thousand Buddhas schools and other members of the City of Ten Thousand Buddhas community.

On the afternoon of the penultimate day, we traveled to Abhayagiri Monastery (Thai Forest Tradition) in Redwood Valley, about 20 miles from the City of Ten Thousand Buddhas. We were welcomed by Ajahn Pasanno, the Abbot, visited several of the kuti (hermitages) on the property, and held our discussion in the recently constructed community center. That evening, about ten members of the group made short presentations at the daily one-and-a-half hour Dharma Talk in the Buddha Hall of the City of Ten Thousand Buddhas. During the course of our three-day meeting, participants also spoke to two classes at the City of Ten Thousand Buddhas high school.

The final session took place on Friday morning when we traveled to Berkeley. There we stopped briefly at Incarnation Monastery, a branch of the Camaldolese monastery at Big Sur, met with the President of the Graduate Theological Union, Dr. James Donahue, and visited Berkeley Buddhist Monastery. After being offered a festive meal at the monastery, the Buddhist monks returned to their respective monasteries and the Catholic monks drove to Big Sur for the annual meeting of the board of directors of the North American Commission for Monastic Interreligious Dialogue.

Monks in the West IV is tentatively planned for July, 2015, possibly at the Abbey of Gethsemani, in tandem with Gethsemani IV. The year 2015 will mark the one-hundredth anniversary of the birth of Thomas Merton, a monk of Gethsemani and one of the pioneers of monastic interreligious dialogue.

--- --- --- --- ---

[1] Michael Casey, Strangers to the City: Reflections on the Beliefs and Values of the Rule of Saint Benedict (Orleans MA: Paraclete Press, 2005), p. 4.

[2] The meaning of Praxis, at least as it is commonly used, is fairly clear. With regard to the other two terms, “Aristotle is not quite consistent in his use of the terms skopòs and télos. But, in summary, I think it is consistent with his intentions to say that every télos (end) is, or could be a skopòs (aim) as well, but not every skopòs is or could be a télos. A skopòs is conscious and intended, and may be set arbitrarily as an aim, and as a causa finalis. A télos or end may be either conscious or subconscious, and it works even unintentionally. It is not arbitrary, but resides in activities as a submerged, enfolded, and implicit causa formalis. It emerges and unfolds through praxis along the continuum from potential (dúnamis) to actualization (enérgeia) (cf. e.g. Metaph.1049b27-1050b5).” Olav Eikeland, The Ways of Aristotle - Aristotelian Phrónêsis, Aristotelian Philosophy of Dialogue, and Action Research(Bern: Peter Lang, 2008), p. 130.

[3] Ibid.

Author

William Skudlarek OSB is Secretary General of DIMMID, a monk of Saint John's Abbey in the United Sates, and currently a member of Trinity Benedictine Monastery, a dependent priory of Saint John's Abbey in Fujimi, Japan.

DIALOGUE AT THE LEVEL OF RELIGIOUS EXPERIENCE / DIALOGUE AU NIVEAU DE L’EXPÉRIENCE RELIGIEUSE

For more Monks in the West 3 photos and text -

Click Here

|