Ven. Thich Thien-An Memorial Page

The Thien-An House / International Buddhist Meditation Center - Los Angeles, CA

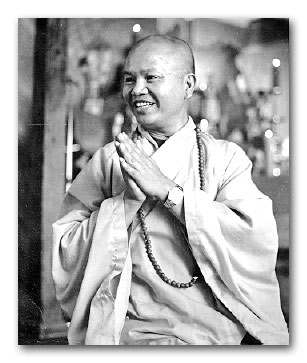

Ven. Thich Thien-An

September, 1926 / November, 1980

*** *** ***

Short Thich Thien-An Bio in PDF - Click Here

Ven. Dr. Thich Thien-An came to Southern California in the summer of 1966 as an exchange professor at UCLA. Soon his students discovered he was not only a renowned scholar, but a Zen Buddhist monk as well. His students convinced Dr. Thien-An to teach the practice of meditation and start a study group about the other steps on the Buddhist path, in addition to the academic viewpoint.Several years later, his enthusiastic followers encouraged Ven. Thien-An to apply for permanent residence and start a meditation center that included place for practitioners to live. Over fifty years later, The International Buddhist Meditation Center continues to thrive.

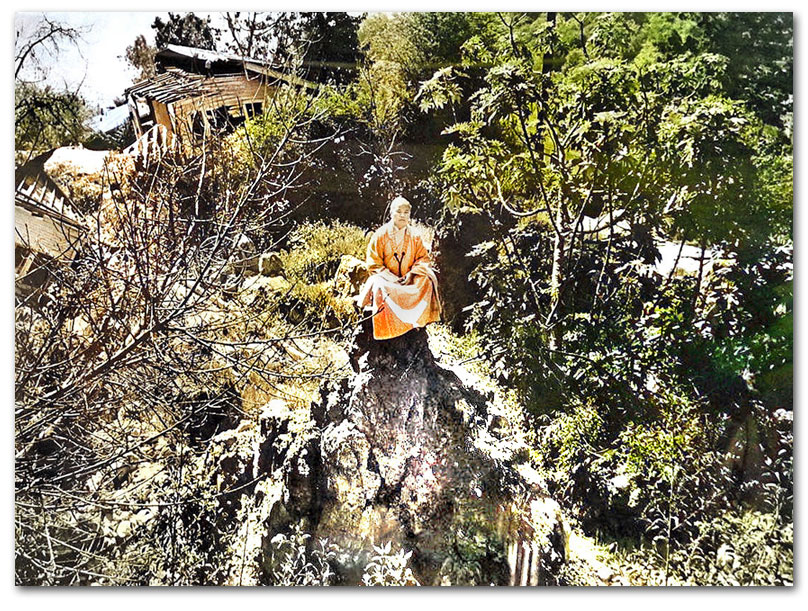

The IBMC today consists of five houses on a residential street several miles west of downtown Los Angeles. Suto, as his students called him, believed in the importance of being accessible to those who face the dukkha of city living. One of the houses in the compound is named for a Vietnamese monk (Thích Quảng Đức) who self-immolated to bring the attention of the world to the horrors of the situation in Vietnam, an act which ultimately led to the downfall of the hated Diem regime.

Suto was born in Hue and grew up in a Buddhist family. Even as a young boy, he would imitate the chanting and ceremony of the monks who came to their house to give blessings and receive dana. He entered the monastery at the age of 14 and continued his education, finally receiving a Doctor of Literature degree at the prestigious Waseda University in Japan. He then returned to Vietnam to found a university there.

Ven. Thien-An's vision of his work in the U.S. was to bring Buddhism into another culture, as always adapting to the national values and understandings. He understood the American mind and culture and had a sense of how the practice needed to differ for Americans to develop. He mentioned often how the West would eventually bring Buddhism back to the East.

When Saigon fell in 1975, Ven. Thien-An saw his responsibility and helped the boat people and other refugees from his homeland. The center became a residence for as many of the displaced as possible. Networking was done to ensure help for the others. The American monks joined with Vietnamese monks to do this Bodhisattva work.

The fleeing Vietnamese, having left all their material belongings as well as family and friends behind, were so relieved to find Buddhists when they got off the ships that many of them cried. Suto opened the first Vietnamese Buddhist temple in the United States. Eventually, he became the First Patriarch of Vietnamese Buddhism in America.

Suto's vision of Buddhism in America included a softening of the lines between different Buddhist traditions, and the Center has always included teachers from Theravada, Mahayana and Vajrayana traditions, as well as monks and students from many different countries. He encouraged interfaith as well as inter-Buddhist activities, and provided opportunities for students who wished to become dharma teachers and continue to live the householder's life, rather than becoming monastics. Many American monks and nuns were also ordained, and a number of his disciples still continue his work, both at the IBMC and other centers.

Dr. Thien-An died at the age of 54 of cancer which had spread rapidly throughout his body, from his liver to his brain. In his last months, one could often find him sitting peacefully on the steps of the bell tower. It was a gift to be able to sit quietly next to him and feel the energy of his understanding. He had many plans but saw the reality of what was happening. He smiled, as he smiled often, a smile of great compassion and loving-kindness for all the world.

Zen Buddhism: Awareness in Action - Thich Thien-An - PDF 30 Pages / Free Download

Read a chapter from Dr. Thien-An's book - Zen Philosophy, Zen Practice

Self-Power and Other-Power

Zen Buddhism emphasizes man's ability to develop himself through his own inner strength and states that by his determination and constant practice he can attain the state of enlightenment and spiritual perfection known as Buddhahood. This reliance upon one's own effort as the way to enlightenment is known as "self-power," and the philosophy of self-power forms the basis for practice in both the Rinzai and Soto schools of Zen. However, Buddhism includes not only the conception of self-power, but also the conception of an "other-power," the compassionate power radiating from the heart of Amita Buddha, the glorified Buddha of the Great Vehicle. The philosophy of the "other-power" provides the central conception of Pure Land Buddhism, a devotional form of Buddhism which flourished in China, Vietnam, Korea and Japan. But the concept of the other-power is not altogether foreign to Zen. In Zen Buddhism there have been attempts to fuse the concepts of self-power and other-power into a synthetic whole, and the result of this synthesis has been very fruitful for both theory and practice.

The union of self-power and other-power runs throughout the practice of Zen in China and Vietnam, and while the two main Japanese Zen sects, Rinzai and Soto, tend to emphasize self-power exclusively, there is a third sect called Obaku Zen, which takes the fusion of the two powers as its basic method of cultivation. Some scholars, such as D. T. Suzuki, do not regard the reliance upon the "other" as authentic Zen, but this author's viewpoint is different. Any method which leads to the calming and purification of the mind and the realization of our true nature can be considered as Zen. Zen is the Japanese equivalent of the Sanskrit word dhyana, "concentration" or "meditation." If the method of combining self-power and other-power as practiced in the syncretic Zen schools leads to the attainment of a concentrated mind and the opening of enlightenment, then that method is legitimate Zen.

The methods of self-power and other-power were both originally taught by Sakyamuni Buddha, the founder of Buddhism. According to the teaching of the Buddha, every living being has a Buddha nature. Therefore, it is within the potential of every man to realize that Buddha nature and to become enlightened. But to reach that state is a tremendously difficult task, calling for dauntless courage and unflinching will power. Thus, very few people are capable of reaching enlightenment by themselves; very few have the required spiritual qualification. For the majority of people it is necessary to rely upon the help of others, and here we find the germ of the "other-power" schools. It is as if a boat were wrecked while floating down a river. Those who are good swimmers would be able to save themselves, but what are they to do who cannot swim as well! They must call for help and rely upon a better swimmer to bring them to the safety of the riverbank. In other words, they must rely upon someone else to save them. Similarly, while we all have the potential to become Buddhas, very few can accomplish Buddhahood through their own unaided striving. Most must rely upon the help of others to reach the safe shore of enlightenment.

In Obaku Zen and the Pure Land schools, practitioners rely upon the compassionate power of Amita Buddha. This may sound rather remote from orthodox Zen, but if we consider the matter carefully, we will find that the difference between Obaku Zen and Pure Land Buddhism on the one hand, and the Rinzai and Soto Zen schools on the other, is only a difference of degree, not of kind. Practice in Rinzai and Soto requires the Master to teach the student how to sit, how to discipline his mind, how to work with the koan or practice shikantaza, and he depends upon the wisdom and spiritual skill of the Master to guide him to enlightenment.

Without the constant prodding of the Master, how many people would reach satori! True, the Zen master cannot give enlightenment, but still he stands as a hand reaching to the disciple from the "other shore," ever ready to extend to him whatever help he requires. Now if the Zen master is able to assist in the struggle to reach enlightenment, then how much more help can we expect from the Master who has reached Perfect Enlightenment, the Buddha! The Zen master can help because he has realized a certain amount of wisdom and compassion. And so the Buddha can provide us with inexhaustible help because he has reached the state of perfect wisdom and infinite compassion. Even the very existence of the path of self-power is in a sense due to the "other-power" of the Buddha. For it was the Buddha who in his compassion taught the path to enlightenment and thereby made that path accessible to mankind. The Buddha is the person who helps us by showing us the Way, and we are the persons who work and practice it by ourselves. That is a union of self-power and other-power. If the self-power and other-power work together to assist each other, then we can go anywhere, reach anywhere we wish. By fusing these two powers in our daily practice, we can enter the gates of enlightenment and abide in the city of Nirvana.

According to the Buddha, there were in the past other Buddhas who were his predecessors, and there will be in the future other Buddhas who will be his successors. The Buddha who is the primary focus of devotion in the Pure Land schools and in Obaku Zen is a Buddha of the remote past called Amita Buddha. Many aeons ago, the story told by Sakyamuni Buddha goes, there lived a Bodhisattva named Dharmakara, who practiced the meditations of compassion and loving-kindness. In his meditation he saw that all living beings are subject to suffering, to the sorrows of birth, old age, illness and death. Witnessing this suffering aroused in him a great compassion, and out of this compassion he vowed that when he attained Buddhahood he would create a special paradise in the Western region where there would be no more suffering. Through the power of his vow he would enable any living being recollecting his name and calling upon his help to be reborn in the Western paradise. Since the Bodhisattva Dharmakara, after several long aeons of self-cultivation, did attain Perfect Enlightenment and become the Buddha Amita, this means that his Great Vow is now a reality. The paradise has been established and is accessible to all who with a mind of sincere faith take refuge in the compassion and grace of Amita Buddha.

The Western paradise is not, however, the final goal for the Pure Land Buddhist, not even for those who seek rebirth there. Rather, it is an intermediary abode where the most favorable conditions for self-cultivation have been set up and secured. While there are some men who by practicing can reach enlightenment in this world, many find difficult obstacles confronting them along the path. The necessity for work, the attractions of the senses, the threat of illness and infirmity and the gross entanglements of materiality all stand as barriers across our path. In the Western Paradise none of these barriers are present. Everything there is radiant, peaceful and beautiful. No defilements can be found, for all shines with purity. Therefore, the country of Amita Buddha is called the Pure Land. Those who are reborn into the Pure Land dwell in the midst of lotus flowers. They are always in the presence of Amita Buddha and the assemblies of Bodhisattvas presided over by the Bodhisattva Kwan-Yin, the embodiment of universal compassion. In the midst of these pure conditions it is easy to develop concentration and wisdom and attain Perfect Enlightenment.

The way to attain rebirth in the Western Paradise is by devotion to Amita Buddha. This devotion is expressed by reciting the sutras that teach about Amita, by chanting His Name, by meditating upon His Image and by calling to mind His Wisdom, Virtue and Compassion. Those who are capable of placing single-minded faith in the Great Vow of Amita will enter the Pure Land where they will meet all favorable conditions for practice and never again fall into this world of suffering. This way is called the "easy path" (Jap. igyo) in contrast to the "difficult path" (nangyo) of self-power. The practice of the "easy path" is very popular in China, Vietnam, Korea and Mongolia, and also in the Pure Land schools of Japan, the Jodoshu and the Jodoshinshu. Belief in the "otherpower" of the Buddha also helps us to develop our selfpower. Therefore, in the Far East a form of practice was developed by Mahayana Buddhists which combines formal meditation with the chanting of the Buddha's name.

In this method the practitioners sit before an image of the Buddha and chant the Buddha's name, quietly and calmly, while at the same time meditating upon the Buddha image or an internalized visualization of the Buddha. As the mind deepens in meditation, a point is reached where subject and object become one. No longer is the Buddha the object and the meditator the subject, but the meditator becomes one with the Buddha. When this happens, this is the state of "One Mind Samadhi," and here there is no longer any distinction between Zen and Pure Land, self-power or other-power, wisdom or compassion, for all has become merged into the brightness of the Infinite Light.

According to a popular Buddhist belief, whenever a person aspires to become a Buddhist, a lotus-flower blossoms in the Pure Land. When a person becomes a Buddhist, this means that he is beginning to practice the way of wisdom, compassion and virtue, so by the operation of the law of cause and effect, in the perfect world created by the compassion of Amita Buddha, a lotus flower, the symbol of inner spiritual awakening, awaits his rebirth into the realm of spiritual perfection. The Western paradise is called the Pure Land because it is the land of purity, and all who are reborn there are pure. Everything in the Pure Land teaches the Dharma. Even the birds sing the songs of the Dharma, the rivers hum sutras as they go flowing by and flowers blossom in harmony with the blossoming of wisdom. In the Pure Land everything is a stepping stone on the way to Perfect Enlightenment.

This concept is similar to the teaching of Zen. In Zen we do not learn only from a book or teacher, but from everything, and we do not learn only in a temple or a meditation center, but everywhere. For Zen is experience itself, the truth of life as it is ever flowing by and encompassing us on all sides. So if we approach life with an open mind, everything can be our teacher. The way of Zen is not a withdrawal from life, but the realization of truth in all the activities of everyday life. We can learn from our fellow men, from the arts. This is why Zen developed the cultivation of such arts as gardening, poetry, painting, tea ceremony and flower arrangement -- as expressions of and keys to the attainment of enlightenment. Zen has even found a vehicle in the martial arts. The first supporters of Zen when it was introduced from China to Japan were the samurai, the warrior class, who found in Zen's emphasis on self-control and equanimity of mind a method of discipline conducive to their own ends. Zen has also influenced the development of techniques of self-defense like judo and karate. The principle underlying these different applications of Zen is that any field of activity can serve as a means for realizing the truth of Zen. In the same way, according to the Pure Land teaching, everything in the Paradise of Amita Buddha is a teacher of the Dharma.

There are three methods of meditation practiced in the combined Zen-Pure Land schools. The first is the chanting of the Buddha's name. The second method is the meditation upon the form of the Buddha. The follower chooses a particularly appealing image of the Buddha and begins by focusing upon that image until he can picture it clearly for himself; then he closes his eyes and tries to visualize the form of the Buddha internally. The third method is to meditate upon the virtues of the Buddha. The Buddha is the embodiment of perfect wisdom and infinite compassion. Either one or both of these virtues together may be taken as the subject of practice. If we choose the compassion of the Buddha, we reflect that the Buddha's compassion makes no distinction between subject and object or between enemies and friends, but pours down upon all equally.

This compassion is different from ordinary love. Ordinary love works according to various discriminations: we love ourselves, but not others; our relatives, but not strangers; our friends, but not enemies. However, the compassion of the Buddha extends equally to everyone. Like the Buddha, we should extend our love and compassion outward to all alike, to everyone everywhere, without making any distinctions. Again, if we choose to meditate on the Buddha's wisdom, we imagine the light of wisdom radiating from the figure of the Buddha and growing larger and larger and brighter and brighter until it merges with our own inner light. At this point we and the Buddha become one. When this stage is reached, then this world will become transformed into the Pure Land, this Samsara become Nirvana, and all the bliss and purity of the Western paradise become realized in the here and now of everyday life. Here the Zen and Pure Land schools meet in that common center from which they both emanate, the One Mind of Buddha, which is our own true and permanent Essence of Mind.

Book - Zen Philosophy, Zen Practice - Ven. Thich Thien-An / Click Here

Also See - "Self Reflection in Zen Buddhism" / Click Here

Ven. Thich Thien-An - Los Angeles, CA

--- --- --- --- ---

A video slide show of Ven. Thich Thien-An and IBMC - The early years. - 1970's

UrbanDharma.org - 2022