|

Opening

a Citadel of Prayer

Their

order facing extinction, 11 Carmelite nuns end decades of solitude

and go dot-com. 'The life we lead, it has to go on,' one says.

By

STEPHANIE SIMON

Times

Staff Writer

August

3 2002

INDIANAPOLIS--Secluded

in a fortress of stone, behind thick, high walls to block the

world, the Sisters of Carmel of the Resurrection pray.

Their

monastery bristles with battlements, commanding a hill. Inside,

the 11 aging nuns walk polished halls in austere silence. Their

retreat is a blankness of white walls without end, of oak doors

shut tight. The only sound is the prayer bell chimes.

The

Carmelites of Indianapolis do not teach or nurse or spread the

faith, as other Roman Catholic sisters do. Private prayer is

their vocation.

Theirs

is not a formal supplication on bended knee. It is a meditation.

They unfold their souls and they wait for words to come. The

sisters pray as they sit in their rocking chairs, watching the

birds peck seeds. They pray as they walk through the courtyard

garden, a tangle of green.

They

venture out of the monastery but rarely. It has been rarer still

for them to invite outsiders in. The isolation has brought

them joy. It has also brought them crisis.

The

Carmelites have not welcomed a new member in a dozen years.

Their average age is 70. Two sisters have died in the last few

months and another is ill.

To

ensure that the contemplative life they cherish will survive

them, the nuns have taken a momentous decision. They have forsaken

the seclusion that defined them.

They

have not given up their two hours a day of private prayer, or

their morning and evening silence. They still celebrate a daily

Mass. They still make a modest living selling altar bread and

prayer books. They still rotate the chores so each sister takes

a turn with the laundry, the cooking and the yard work.

But

the Carmelites of the Resurrection have opened up their fortress.

It has been a startling journey. Nuns of such simplicity

that they live on $1 a day have put their future in the hands

of an ad agency famous for fast-food commercials. Sisters

who were once so isolated they didn't know the Vietnam War had

begun have requested advice from the security director for the

NFL's Indianapolis Colts--who gave them all team T-shirts.

The

Carmelites hired a part-time development director, Linda Hegeman,

to represent them. She rounded up an advisory board of two dozen

prominent citizens, each with a skill she thought might help

the sisters navigate a world they had long since left behind.

The

advisors--most but not all Catholics--included a software designer,

a public relations specialist, an administrator from the local

Catholic college and a former city police chief, now working

security for the Colts. The group is eclectic, but effective:

Meeting every month or two, its members pushed the nuns to move

beyond their original vision of a promotional brochure to consider

a punchy online campaign that had them posting their private

prayers on the Internet.

Timid

at first, the sisters prayed over each suggestion--and ended

up taking most of them, with gusto. They now consider their

advisors as friends, hosting pizza parties for the board inside

the monastery.

"It

has been a stretch," Sister Joanne Dewald says.

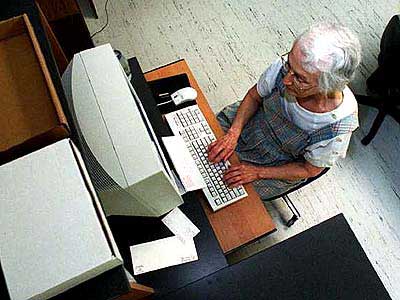

In

the arched hallways of the monastery they helped build, the

sisters with hearing aids and white hair are determined to keep

stretching. They have discovered unexpected joy in engaging

the world. Their revolution has enriched their faith. It has

also brought them hope for a future. Nearly halfway through

a five-year outreach plan, the Carmelites are speaking with

several young women who might be interested in joining.

"The

vocation is so dear to us," says Sister Rachel Salute,

76. "To see it dying out.... " She stops. She has

been a Carmelite nun since 1953.

"You

would go to such extremes," she says, "to prevent

your community from dying."

"The

life we lead, it has to go on," says Sister Ruth Ann Boyle--at

age 45 the youngest by two decades. "Just as much as the

work of teachers or nurses needs to go on, the life of prayers

must go on."

"It's

a calling. It's a service," Sister Joanne says. As a girl,

she dismissed the Carmelites as "loony." Now 72, she's

the monastery prioress--and she is convinced that when women

give their lives to prayer, their devotion can help heal the

world. "It's hard to explain this life. It doesn't make

much sense," she says. "But you're drawn to it."

Sister

Joanne first suggested several years ago that the nuns consider

reaching out to young women who might feel that same mysterious

call.

The

concept was not novel. As the number of nuns in the United States

has plunged--from 180,000 in 1965 to fewer than 74,000 today--many

orders have tried marketing. Dominican nuns in Michigan ran

a commercial on "The Oprah Winfrey Show" with the

tagline: "Life is Short. Eternity Isn't." The Sisters

of Mercy in New York advertise in bus shelters, asking: "Do

You Have a Call Waiting?"

For

the Carmelites, though, self-promotion did not come easy.

Like

other cloistered sisters--there are at most 4,000 in the U.S.--the

Carmelites of Indianapolis live sparingly, eating but one cooked

meal a day and sleeping in barren cells with barely enough room

for a bed, a desk and a chair.

For

decades, they were so sequestered that neighbors had no idea

whether nuns or monks lived behind the imposing turrets. The

nuns could not leave the monastery, even to visit a dying parent.

Relatives could visit just one hour a month, talking to the

sisters through an iron grate so thick, even fingertips could

not touch.

The

nuns' main interaction with outsiders took place through the

"turn," a wooden cabinet set on a turntable at the

front door of the monastery. Visitors would place messages or

packages in the cabinet. A veiled sister on the other side of

the wall would spin it, wordlessly, to her. Sometimes, to the

nuns' discomfort, Catholic parents seeking a blessing would

place a baby in the cabinet. The sister inside would offer a

hasty prayer, then whisk the newborn back.

That

extreme isolation began to ease in the late 1960s, when the

Second Vatican Council called for reforming church life and

its rituals.

The

nuns started shopping for groceries instead of having them delivered.

They ordered their first newspaper subscription. They even began

opening their morning Mass to local Catholics; on weekdays,

a dozen visitors might gather with them behind the blue glass

doors of the chapel.

Even

now, however, the nuns keep their forays to the outside world

brisk: They buy groceries at Sam's Club (or pick up Subway sandwiches

as a treat) and then promptly return. They don't stop to chat.

They don't go out for fun. They shun what they call "clutter"--any

interaction that distracts them from prayer. Sister Joanne still

turns down invitations to address young women at the Catholic

college down the street.

So

it was a remarkable leap when--at the suggestion of their development

director--the sisters invited half a dozen executives from the

ad agency Young & Laramore to the monastery two years ago

to discuss marketing.

They

met in the reading room, the only space in the cloister that

has been decorated--with a crystal wind chime, a black-and-white

ink drawing of a mountainous landscape, a straight-backed couch

with thin pillows. The sisters gather there in a circle to pray

aloud each morning. They were uneasy letting strangers in.

The

executives were a bit uneasy, too. They expected the sisters

might be slightly dotty from their self-imposed exile. Instead,

they found them witty, incisive, even irreverent.

In

their younger years, in full black habits, the nuns drove bulldozers,

dug postholes and hammered roof beams to build the monastery.

Now, in sandals and sundresses from Goodwill, they drink diet

Mountain Dew and wrestle pillows from their black Labrador retriever,

Lucy. They watch documentaries on ancient Greece. Also, "Karate

Kid II."

They

write prayer books with inclusive language (referring to God

as "you" instead of "master"). They joke

about their years of suffering in virtual quarantine. They even

mock their own devotion to two hours a day of private prayer.

"What

am I thinking about? I'm thinking I see a leak in the roof over

there. I'm thinking, why has this stock gone from $95 to $2,"

says Sister Betty Meluch, 70, laughing.

After

an hour with the sisters, Paul Knapp, president of Young &

Laramore, was captivated. He volunteered at once

to take on--free--the job of selling the nuns to the world.

His firm had scored big with clever ads that made Goodwill

clothes hip and Steak & Shake burgers saucy. The nuns were

an irresistible challenge. All he needed was a hook.

"Whether

it's a steak burger or a nun, [you have to ask] 'What do you

want people to think of when they see them?' It's all about

strategic positioning," said Tom Denari, an agency vice

president.

Searching

for that hook, the marketing team asked the nuns: "So,

what do you do?"

"We

pray," the sisters replied.

"What

do you pray?"

"We

pray the news."

Indeed,

the sisters devour current events. They read Time, Atlantic

Monthly, the Economist, National Geographic, Arthritis Today.

Often, a sister will don headphones during morning prayers

to catch National Public Radio. After Mass (led by a visiting

priest), they take turns discussing world events that merit

special prayer.

The

ad team wanted to play off that passion. In a flash of inspiration,

http://praythenews.com

was born.

The

interactive Web site offers Carmelite history and a prayer of

the day. The nuns post a sample daily schedule (feed the birds,

pray, change oil in the Taurus), and essays explaining the contemplative

life.

The

heart of the site is the News Perspective page, where sisters

post essays about current events--from famine in Eritrea to

pedophilia in the church, from corporate scandals to the temper

of basketball coach Bobby Knight.

"It's

like we're raising our antenna, so if someone out there has

a calling to this life and is raising her own antenna, we might

be able to communicate," says Sister Terese Boersig, 69.

Since

http://praythenews.com was launched in March 2001, the site

has logged more than 12 million hits. Many readers return once

a week to read Sister Betty's take on the Taliban or see what

Sister Joanne has to say about Iraq.

Virtual

visitors from around the globe have e-mailed prayer requests

to the Light a Candle page. Those prayers have opened the nuns'

eyes to the struggles they left behind when they took their

vows of poverty, obedience and chastity. So many asking for

help finding jobs, Sister Ruth murmurs. So many asking for help

finding love.

More

than three dozen women have contacted Sister Joanne online

to talk about Carmelite life, including eight who seem genuinely

drawn. One woman explained that the Web site had awakened the

same joyous feeling she felt when she prayed at the monastery

years before. "It made me wonder once again," she

wrote, "whether I am called to religious life."

The

outreach campaign forced the sisters to wrestle with the modern

world in ways they had never imagined.

They

have prayed much over whether to sell their books through the

Web site. They reluctantly agreed--on advice from Mike Zunk,

the Colts security chief--to conduct background checks on any

woman who applies to enter the monastery.

Most

dramatic, the sisters have found themselves, for the first time,

under pressure to produce something.

The

nuns who write the News Perspective face a deadline every Monday.

They dread it. For years, they have let their thoughts unroll

in languor. As they put it, they have focused on being, not

doing. Now, they must direct their musing to a particular topic,

then commit their prayers to paper. "A chore," Sister

Joanne calls it.

Yet

the sisters cannot imagine again withdrawing behind the veil.

"This

is transformative," Sister Terese says. "We're not

going back."

Adds

Sister Joanne: "I don't think we could."

The

nuns have found joy in breaking down their cloister. For years,

they were convinced that steeping their souls in solitude brought

them closer to God. Now, they find spiritual strength from their

readers' words on the Web site.

As

they pray for a mother to recover from cancer, for an end to

civil war, for a raise, for a safe journey, the Sisters of Carmel

of the Resurrection feel they are performing a great service.

They

no longer pray for the world. They pray with it.

|